How Is Mustard Made?

From tiny seeds to tangy condiment through enzymatic reactions and grinding.

The Overview

Mustard is produced by grinding mustard seeds with liquid (water, vinegar, or wine) and spices, triggering an enzymatic reaction that creates the condiment’s characteristic pungency and heat.

The manufacturing process is deceptively simple—just seeds, liquid, and grinding—yet produces dozens of varieties from mild yellow mustard to sharp Dijon through careful control of grinding temperature, fermentation time, and seed selection.

Here’s exactly how tiny seeds transform into the iconic yellow, brown, and spicy varieties through chemistry and industrial precision.

🥘 Main Ingredients (Varies by Type)

• Yellow mustard seeds (for mild mustard)

• Brown or black mustard seeds (for spicy varieties)

• Vinegar or wine (white, apple cider, or cider vinegar)

• Water

• Salt

• Optional: turmeric, paprika, spices, honey

Step 1: Mustard Seed Harvesting & Drying

Mustard plants grow in dry, continental climates—predominantly Canada, Ukraine, and Eastern Europe—and are harvested when seed pods mature and dry in the sun.

Mechanical harvesters cut the plants, separate seeds from pods, and collect them in bulk.

Seeds are dried in large silos to remove moisture, then sorted and cleaned to remove debris, rocks, dirt, and twigs before transport to the processing facility.

Step 2: Cleaning & Sorting at the Factory

Fresh seeds arrive at the mustard factory and pass through electronic sorting machines that use optical scanners to remove damaged or discolored seeds.

Air blowers and magnetic separators remove remaining debris, twigs, and any iron contaminants (from equipment wear or environmental pickup).

Multiple quality checkpoints ensure only the finest seeds proceed—seed quality directly determines the final mustard’s flavor intensity and color.

Step 3: Seed Preparation & Optional Pre-Treatment

Cleaned seeds may be briefly soaked in water to soften them before grinding, or toasted at low temperature (40-50°C) for 10-20 minutes to develop deeper, more complex flavors.

For Dijon mustard, seeds are often cracked or cut to separate them from their husks—this reduces husk content to no more than 25%, creating the silky texture authentic Dijon is known for.

Seed preparation varies dramatically by mustard type—yellow mustard uses minimal pre-treatment, while Dijon and specialty varieties undergo more elaborate preparation.

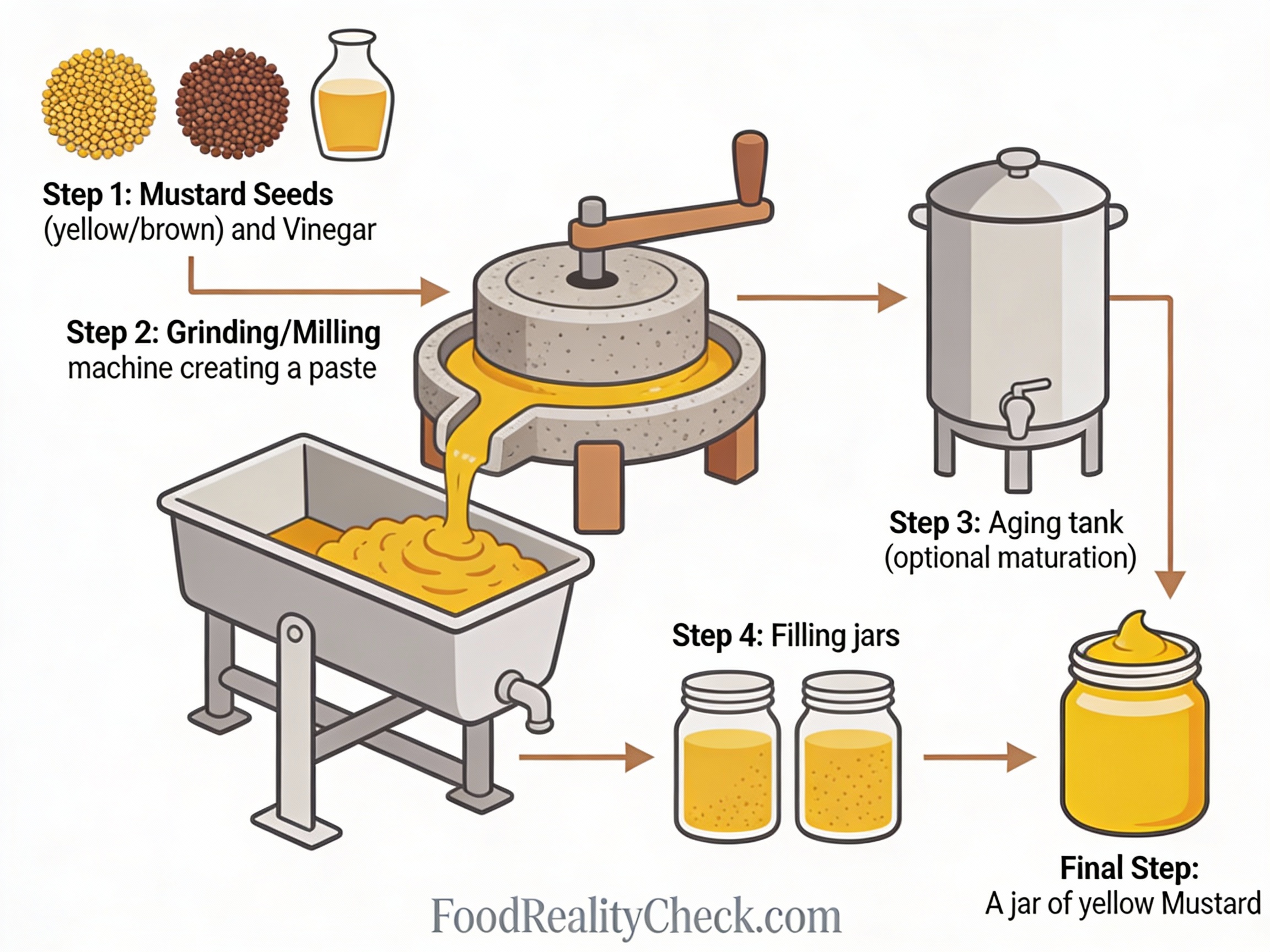

Step 4: Mixing the Dry & Liquid Ingredients

In large mixing tanks, cleaned mustard seeds are combined with water, vinegar, salt, and other seasonings (turmeric for yellow mustard, paprika for certain varieties, spices for flavored mustards).

For yellow mustard, this happens in a single batch; for Dijon, seeds may soak in liquid for 8-24 hours before grinding to develop pre-fermentation flavors.

The ratio of seeds to liquid varies by mustard type—yellow mustard uses roughly 1 part seeds to 1 part water/vinegar; Dijon uses more seeds and less water for thicker, sharper results.

Step 5: Fermentation (Dijon & Premium Varieties Only)

For authentic Dijon mustard, the seed-liquid mixture undergoes fermentation in stainless steel tanks at 15-25°C for 12-48 hours.

During fermentation, natural microbes and the myrosinase enzyme slowly develop the robust, complex flavors that distinguish Dijon from other mustards.

Yellow mustard typically skips fermentation entirely, heading straight to grinding for faster, milder results (20 hours total production vs. 32+ hours for Dijon).

Grinding: The Heart of Mustard-Making

Step 6: Stone Mill or Disc Mill Grinding

The seed-liquid mixture is pumped into industrial grinders—traditionally stone mills with rotating millstones, or modern corundum disc mills with counter-rotating discs.

As seeds are crushed between the grinding surfaces at precise gap widths (typically 0.5-2mm), the myrosinase enzyme is activated, triggering the enzymatic reaction that creates mustard’s signature heat and pungency.

The grinding process is carefully timed—typically 10-30 minutes—because extended grinding causes the enzymatic reaction to peak and then fade, reducing the final mustard’s sharpness.

Step 7: Temperature Control During Grinding

Grinding generates significant heat—temperatures can reach 50-65°C inside the mill if not carefully controlled.

For milder mustard, higher temperatures are desired (which slow the myrosinase enzyme), while cooler temperatures preserve maximum pungency.

Modern industrial mills use water-jacketed chambers that circulate cool water around grinding discs to maintain precise temperature throughout the process.

Step 8: Halt of Enzymatic Reaction

Once the desired heat level is achieved, the myrosinase enzyme must be deactivated to stop the enzymatic reaction.

This happens naturally through one of two mechanisms: temperature rise (which denatures the enzyme above 60°C), or acid addition—vinegar’s acidity slows the enzyme reaction dramatically.

Timing this halt is critical—too early and mustard lacks sharpness; too late and it becomes overly harsh and bitter.

Step 9: Texture Fine-Tuning (Smooth vs. Whole-Grain)

After initial grinding, the mustard paste can take two paths depending on final product desired:

Smooth mustard (Yellow, Dijon): Passes through fine grinding mills or colloid mills that break seed particles into microscopic sizes (2-40 microns), creating silky-smooth texture with no visible particles.

Whole-grain mustard: Stops after coarse grinding, leaving partially intact seeds visible in the paste for rustic texture and bursts of whole-seed flavor.

Step 10: Maturation & Aging

After grinding, the mustard paste is cooled to 15-25°C and rests in tanks for 1-4 weeks (Dijon often requires longer aging than yellow mustard).

During maturation, flavors meld, harsh edges mellow, and the texture stabilizes. Acid components (from vinegar) soften, creating a more balanced, integrated taste.

Some premium producers extend aging to 8+ weeks for maximum complexity, though commercial producers typically optimize for 1-2 weeks to balance quality with production efficiency.

Step 11: Quality Control & Standardization

Matured mustard is tested for color consistency (measured by spectrophotometer), heat intensity, acidity (pH), viscosity, and flavor profile using trained sensory panels.

Batches are standardized—if one batch is too sharp, it’s blended with a milder batch; if color is off, natural colorants are added to match the standard.

This ensures every jar of a specific mustard variety tastes and looks identical to every other, regardless of which batch or factory produced it.

Preservation, Bottling & Distribution

Step 12: Optional Pasteurization

Some commercial mustards are gently heated to 85-90°C for 10-30 seconds to kill any remaining microorganisms and extend shelf-life.

Pasteurization slightly muffles the sharp heat of fresh mustard, which is why artisanal, unpasteurized mustards taste noticeably spicier than commercial supermarket varieties.

Many premium mustards skip pasteurization to preserve maximum flavor intensity, accepting slightly shorter shelf-life as a trade-off.

Step 13: Filling into Bottles or Tubes

Mature mustard is pumped into glass jars, plastic bottles, or squeezable tubes at high speed—modern filling lines process 300-500 containers per minute.

Fill volumes are precisely controlled to 6oz (170ml), 8oz (227ml), or other standard sizes with accuracy better than ±1%.

Containers are sealed with caps, lids, or tube crimps immediately after filling to prevent oxygen infiltration and preserve freshness.

Step 14: Labeling & Batch Coding

Filled bottles move to labeling machines that apply nutrition facts labels, ingredient lists, and manufacturer information at high speed.

Batch codes and “best by” dates are printed using laser marking systems, enabling traceability and recall capability if needed.

Vision inspection systems verify label placement, legibility, and proper sealing before products leave the production line.

Step 15: Case Packing & Storage

Labeled mustard jars are robotically packed into cardboard cases (typically 12-24 jars per case) and arranged on pallets.

Cases are wrapped with plastic film and stored in climate-controlled warehouses at room temperature or cool conditions.

Mustard’s natural acidity (pH 3.0-4.0) and salt content provide natural preservation, allowing unopened bottles to remain shelf-stable for 12-24 months.

Why This Process?

Careful temperature control during grinding preserves or reduces heat intensity depending on desired product—yellow mustard needs controlled heating to reduce sharpness, while spicy brown mustard needs cool grinding to preserve maximum pungency.

Fermentation develops complex flavors through natural microbial activity, creating the robustness that distinguishes Dijon from simpler yellow mustards.

The myrosinase enzyme’s enzymatic reaction is the critical chemical process—controlling when it’s activated and when it’s halted determines the final mustard’s character.

What About Additives & Variations?

Different mustard varieties use different seed types and ingredients:

• Yellow mustard: White mustard seeds + turmeric + water + white vinegar = mild, bright yellow

• Dijon mustard: Brown mustard seeds + white wine + fermentation = sharp, sophisticated flavor

• Whole-grain mustard: Coarsely ground brown seeds + vinegar = rustic texture with seed bursts

• Spicy brown mustard: Brown seeds + minimal water + longer grinding = intensely hot

Commercial mustards may contain minor additives:

• Gum arabic or xanthan gum – for texture stability

• Turmeric or paprika – for color

• Honey or sugar – for sweetness balance

• Natural or artificial flavors – for depth

Premium artisanal mustards contain only seeds, vinegar, water, and salt—nothing more.

The Bottom Line

Mustard production is a deceptively simple process—seeds, liquid, grinding—yet produces dramatically different results based on seed type, liquid choice, grinding temperature, and fermentation time.

The myrosinase enzyme’s enzymatic reaction is the chemical magic that transforms dormant seeds into pungent condiment, and controlling this reaction is the mustard-maker’s primary skill.

Now you understand exactly how tiny mustard seeds become the sharp, tangy, heat-generating condiment through enzymatic reactions and careful industrial precision.