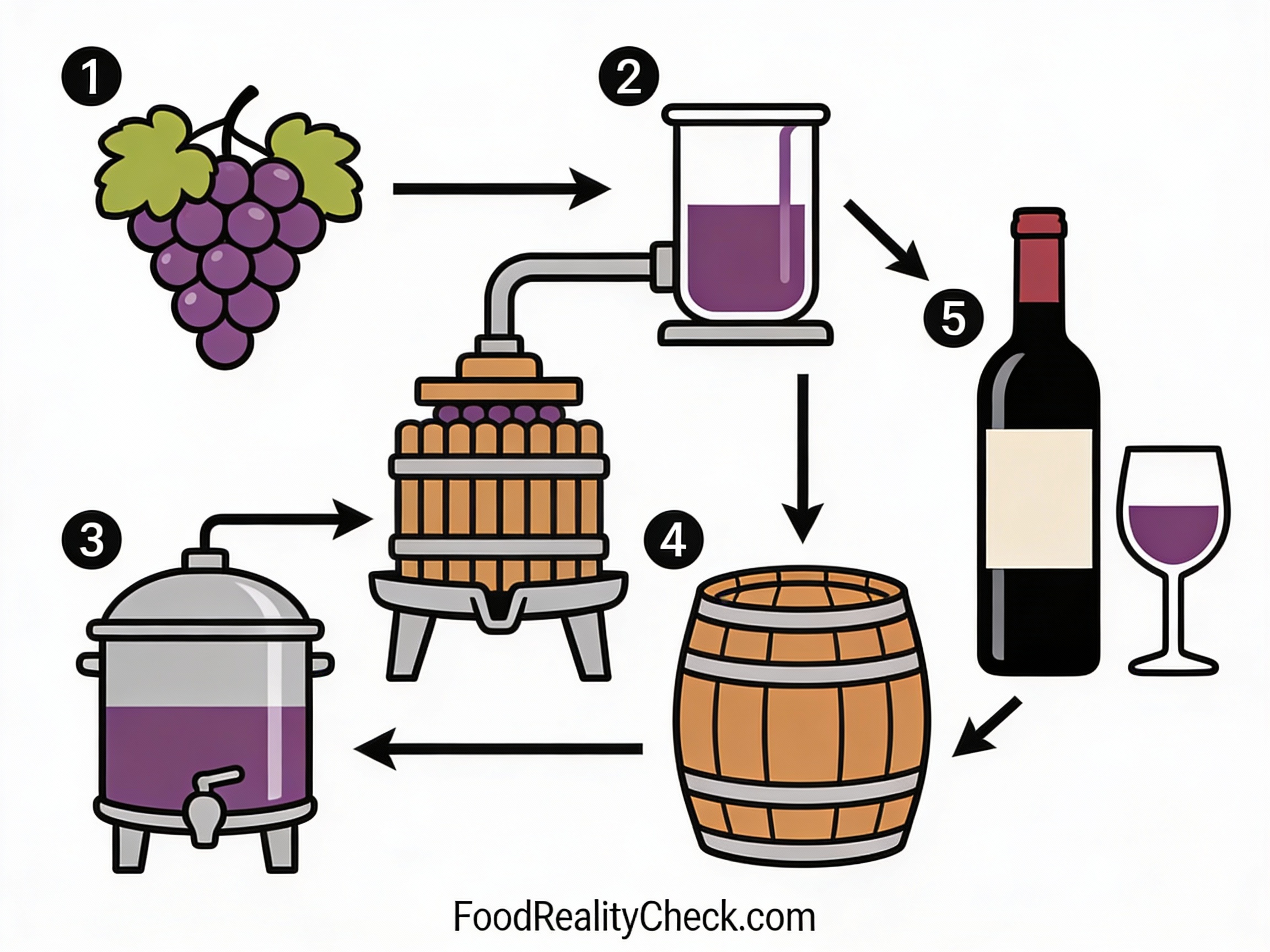

How Is Wine Made?

From grape harvest to fermentation through yeast metabolism and aging.

The Overview

Wine is made by harvesting grapes, crushing them to release juice, fermenting the juice with yeast that converts sugars into alcohol and CO₂, aging the resulting wine to develop flavor, and bottling it for distribution—a process that relies entirely on natural microbes and chemical reactions to transform simple fruit juice into a complex, shelf-stable beverage.

The manufacturing process is fundamentally a controlled fermentation—wild or cultured yeast consumes the natural sugars in grape juice, producing alcohol (typically 12-15% by volume), and the wine matures for months to years as complex flavor compounds develop through oxidation, polymerization, and microbial metabolism.

Here’s exactly how grapes transform into wine through fermentation, aging, and careful chemical management.

🥘 Main Ingredients & Materials

• Grapes (specific varieties for specific wine types)

• Yeast (wild or cultured Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

• Sulfur dioxide (preservative, antimicrobial)

• Optional: fining agents (egg white, gelatin for clarification)

• Optional: oak chips or oak barrels (for aging and flavor)

Step 1: Grape Selection & Harvest Timing

Grapes are harvested at precise ripeness—measured by sugar content (Brix), acidity (pH), and phenolic maturity (tannin development).

Optimal harvest timing is critical: underripe grapes produce thin, acidic wine; overripe grapes produce flabby, alcohol-heavy wine with lost acidity.

Different grape varieties are harvested at different optimal times—cool-climate regions harvest earlier (higher acidity, lower sugar); warm regions harvest later (higher sugar, lower acidity).

Step 2: Crushing & Destemming

Harvested grapes are transported to the winery and fed into a crusher-destemmer machine that breaks the grape skins while separating grapes from stems.

Crushing breaks cell walls, releasing juice and exposing it to yeast and oxygen.

Destemming removes astringent tannins from stems that would create harsh mouthfeel (though some winemakers leave stems on for increased tannin extraction).

💡 Did You Know? Grapes naturally contain yeast on their skins—wild Saccharomyces cerevisiae that can spontaneously ferment juice without any added yeast culture. Traditional winemaking relied on these wild yeasts; modern commercial winemaking typically inoculates with cultured yeast strains to ensure consistent, predictable fermentation and avoid spoilage organisms.

Step 3: Sulfur Dioxide Addition (Preservative & Antimicrobial)

Sulfur dioxide (SO₂) is added to crushed grapes at 20-150 mg/L depending on desired effect—it kills spoilage bacteria and wild yeasts, prevents oxidation, and protects color and flavor.

SO₂ is controversial but nearly universal in winemaking—it’s the only reliable way to prevent bacterial spoilage and oxidation that would ruin the wine.

After SO₂ addition, the winery waits 24-48 hours before yeast inoculation, allowing SO₂ to eliminate unwanted microbes.

Step 4: Yeast Inoculation & Primary Fermentation Begins

Cultured yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae or other strains selected for specific flavor characteristics) is added to the crushed grape juice (called “must”).

Yeast cells metabolize grape sugars (glucose and fructose, typically 15-25% of juice by weight) through fermentation, producing ethanol (alcohol) and CO₂ gas.

The fermentation is exothermic—heat is released as a byproduct, raising temperature from 15°C to 25-30°C depending on yeast activity and ambient conditions.

Step 5: Active Fermentation (Days to Weeks)

During primary fermentation (typically 5-30 days depending on temperature, yeast strain, and sugar content), yeast vigorously consumes sugars while producing CO₂ gas that creates visible bubbling and foam.

Temperature is carefully controlled—cool fermentation (15-18°C) produces more aromatic, delicate wines; warm fermentation (25-30°C) produces fuller-bodied, riper wines.

Winemakers monitor fermentation by measuring specific gravity (sugar content) daily—fermentation is complete when all or most sugars are consumed and specific gravity stabilizes.

Step 6: Fermentation Management (Punch-down or Pumping-over)

For red wines made with grape skins present (which float to the top during fermentation), the winemaker must punch down the floating skins 1-2 times daily or pump fermenting wine over the skins to keep skins in contact with juice.

This “punch-down” or “pump-over” serves multiple purposes: keeps skins submerged, prevents mold/vinegar bacteria from infecting exposed skins, and extracts color and tannins from skins.

For white wines (made from juice only, without skins), this step is unnecessary.

💡 Did You Know? Red wine gets its color from anthocyanins—pigments in grape skins that dissolve into the juice during fermentation. White wine doesn’t contact skins during fermentation, so it remains clear/pale yellow. Rosé wine contacts skins briefly (a few hours to a few days), resulting in its characteristic pink color. The color difference is entirely about skin contact time during fermentation—the same white grape varieties can produce red or white or rosé wine depending on winemaking choices.

Step 7: Fermentation Completion & Yeast Settling

Fermentation is complete when sugar levels drop to <2 g/L (most fermentable sugars consumed) and yeast cells die or become dormant, settling to the bottom as sediment (lees).

The wine is now roughly 12-15% alcohol by volume (depending on initial grape sugar content).

At this point, the wine is technically complete but still extremely rough and unbalanced—it requires aging to develop flavor and complexity.

Aging & Development: Creating Complexity

Step 8: Malolactic Fermentation (Optional Secondary Fermentation)

Many red wines and some white wines undergo malolactic fermentation—a secondary fermentation where lactic acid bacteria convert harsher malic acid into milder lactic acid.

This fermentation softens the wine’s acidity and creates additional complexity through bacterial metabolism.

Malolactic fermentation is optional—some winemakers want it, others prevent it by keeping SO₂ and temperature low to inhibit bacteria.

Step 9: Aging in Stainless Steel or Oak Barrels

After primary fermentation, wine is transferred to aging vessels: stainless steel tanks (inert, preserves fruit flavors), neutral oak (minimal flavor impact), or new oak (imparts vanilla, spice, toast flavors).

Aging duration varies: light wines (Pinot Grigio) age 2-4 months; fuller wines (Cabernet Sauvignon) age 12-24+ months or longer.

During aging, oxidation reactions and polymerization slowly develop color, soften tannins, and create complex secondary flavors—this is why aged wines taste completely different from fresh wine.

Step 10: Racking (Sediment Removal)

Every 3-6 months during aging, wine is “racked”—carefully siphoned from one container to another, leaving behind sediment (dead yeast, tannin polymerization solids) that has settled to the bottom.

Racking removes harsh flavors from extended yeast contact, clarifies the wine, and provides oxygen exposure that encourages oxidation reactions during aging.

Traditional winemaking uses gravity-fed racking; modern wineries use inert gas (nitrogen) to help siphon wine without oxygen exposure.

Step 11: Clarification (Fining & Filtration)

Before bottling, wine is clarified to remove remaining suspended solids (yeast particles, proteins, tannin polymers).

Clarification is accomplished through fining—adding substances like egg white, gelatin, or bentonite clay that bind to suspended particles, causing them to clump and settle—followed by filtration through cloth or paper.

Some premium winemakers skip filtration to preserve delicate flavors, accepting slight cloudiness; most commercial producers filter for crystal clarity.

Step 12: Final SO₂ Addition (Preservation for Bottling)

Before bottling, additional SO₂ is added at 30-100 mg/L to prevent oxidation and microbial spoilage during bottle aging.

This final SO₂ addition is critical—without it, wine would oxidize in the bottle and develop off-flavors within months.

The amount added depends on desired aging potential—wines meant for long-term aging (20+ years) receive higher SO₂ dosing.

Step 13: Bottling

Clarified, stabilized wine is filled into bottles (typically 750ml standard bottles) using automated filling machines at 1,000+ bottles per hour in commercial wineries.

Bottles are filled to precise levels (typically 75mm of headspace at top) to ensure proper oxygen levels in the bottle—too little headspace causes pressure issues, too much allows excessive oxidation.

The wine is cooled before bottling to ensure stability during the filling process.

Step 14: Corking or Capping & Sealing

Filled bottles are immediately sealed with cork, screw cap, or synthetic stopper.

Cork is traditional for premium wines (can age 10-50+ years); screw caps are increasingly popular for modern wines (no cork taint risk, excellent for young wines meant for early drinking).

Proper sealing is critical—oxygen exposure through loose closures causes oxidation and spoilage.

Step 15: Labeling & Packaging

Sealed bottles are labeled with brand/producer name, wine type, vintage (harvest year), region of origin (regulated by appellation laws), alcohol content, and producer information.

Label design reflects wine style—premium wines have elegant, detailed labels; budget wines have simple labels.

Bottles are packed into cases (typically 12 bottles per case) for distribution.

Step 16: Storage & Distribution

Bottled wine is stored horizontally in cool, dark conditions (13-15°C) to keep corks moist and minimize oxidation.

Wine is distributed via temperature-controlled trucks to retailers and restaurants.

Shelf-life varies: light, young wines should be consumed within 1-3 years; premium wines can age for decades if stored properly.

Why This Process?

Fermentation converts sugars into alcohol—a preservative that prevents bacterial spoilage and creates shelf-stability lasting decades.

SO₂ addition prevents oxidation and kills spoilage microbes that would create vinegar or off-flavors.

Aging allows oxidation reactions and tannin polymerization to develop complexity and soften harsh components.

Racking removes harsh yeast byproducts while providing controlled oxygen exposure for optimal aging.

Wine Types & Style Variations

Wine style is determined by multiple factors:

• Grape variety: Chardonnay, Cabernet, Pinot—each has distinct flavor profile

• Fermentation temperature: Cool = aromatic, crisp; warm = full-bodied, ripe

• Yeast strain: Different strains produce different flavor compounds and alcohol levels

• Oak aging: New oak = vanilla, spice; neutral oak = minimal impact

• Malolactic fermentation: Yes = softer, richer; No = crisper, sharper

• Residual sugar: Dry = all sugars consumed; sweet = sugars remain

Different regions produce distinctive wine styles through climate, grape varieties, and traditional winemaking methods (regulated by appellation laws like Bordeaux, Burgundy, Chianti, etc.).

The Bottom Line

Wine production is fundamentally a controlled fermentation and aging process—yeast converts grape sugars into alcohol, and time develops complexity through oxidation and chemical reactions.

The winemaker’s art lies in managing temperature, oxygen exposure, and timing to guide fermentation and aging toward desired final flavor profile.

Now you understand exactly how grapes become wine through fermentation, aging, and careful chemical management—a process combining ancient tradition with modern science.