What Are Heavy Metals in Fish?

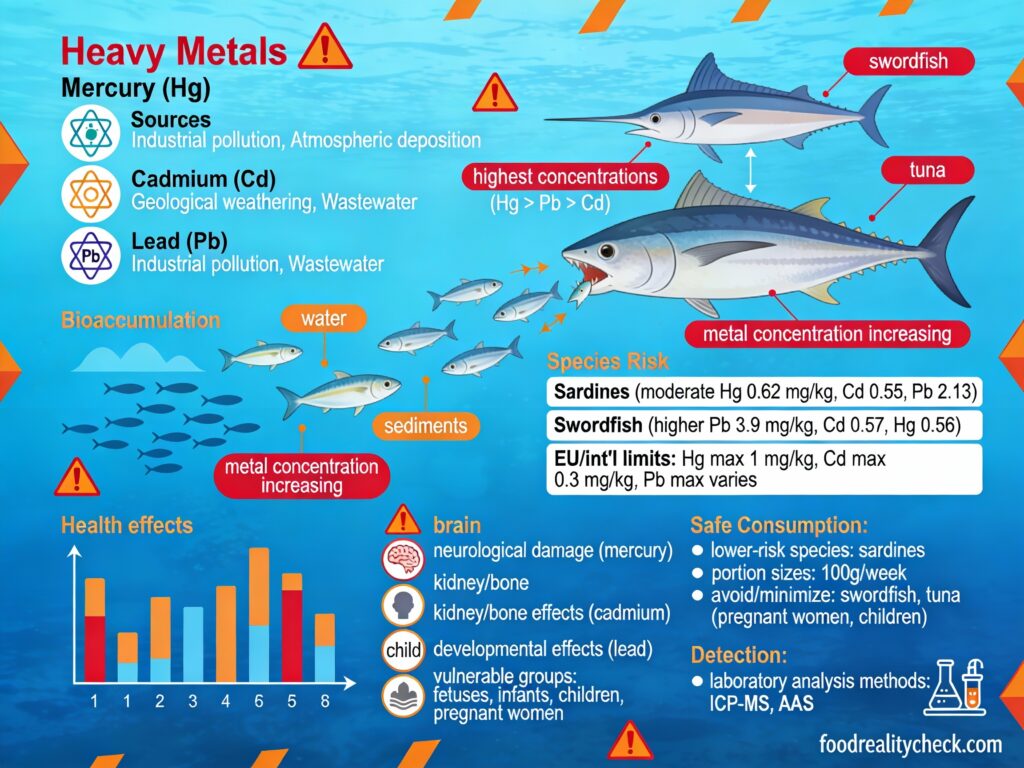

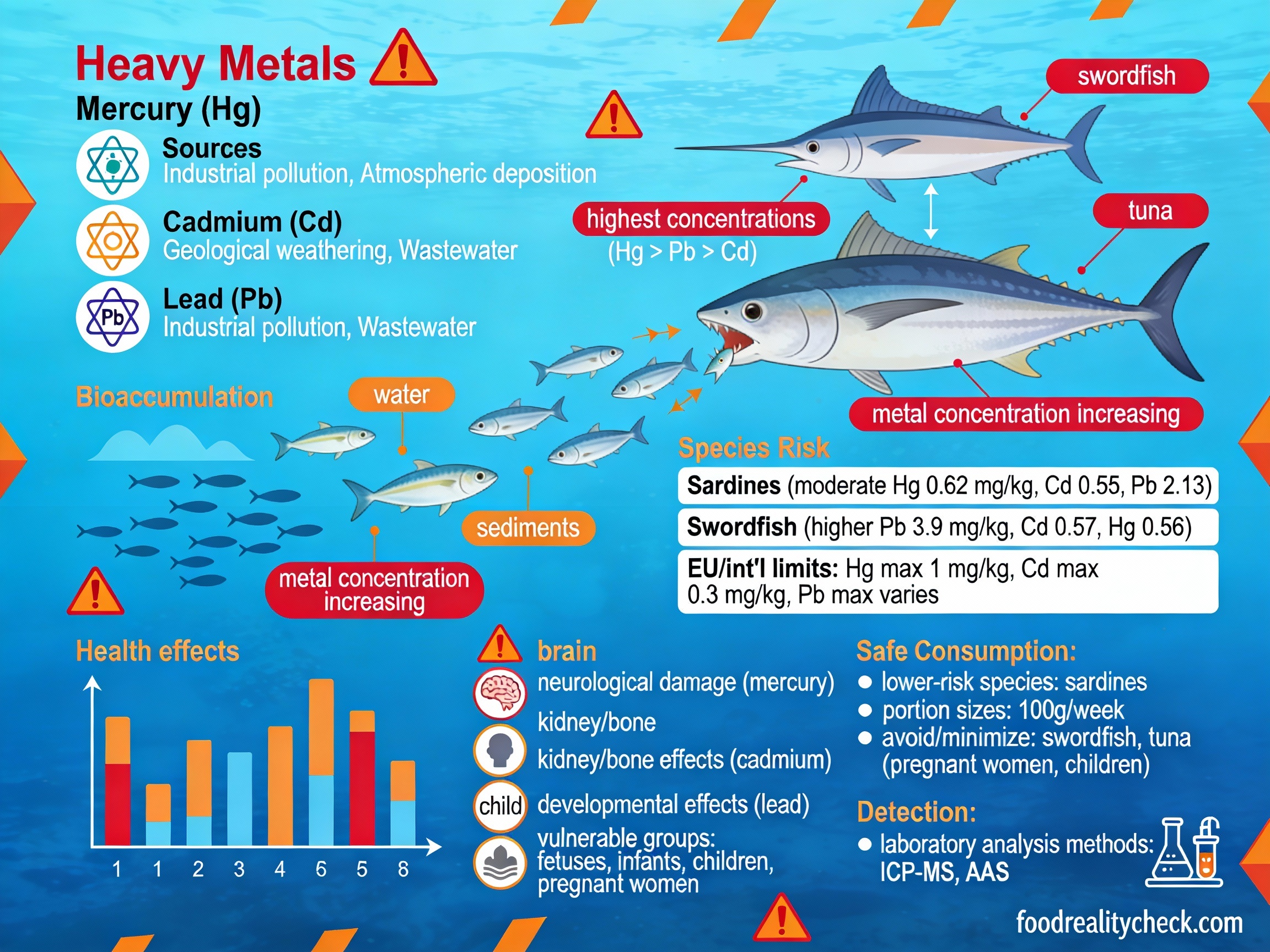

Heavy metals are natural elements found in water, sediment, and the environment. The main ones of concern in fish are mercury, lead, cadmium, and arsenic.

While these metals occur naturally, industrial pollution and coal-burning emissions increase their levels in our oceans and waterways. Once in the water, these metals don’t break down—they accumulate in fish tissues over time.

Quick Facts About Heavy Metals in Fish

- Primary concern: Mercury (especially methylmercury, the organic form)

- Main source: Industrial emissions, mining, and natural deposits

- Process: Bioaccumulation and biomagnification up the food chain

- Most affected fish: Large predatory species and long-lived fish

- Regulated by: FDA (USA) and EFSA (Europe)

How Does Fish Get Contaminated with Heavy Metals?

Bioaccumulation: Fish absorb heavy metals from the water and food they consume. Over their lifetime, metals accumulate in their tissues.

Biomagnification: This is the key issue. Larger, predatory fish eat smaller fish that already contain mercury. The mercury concentrates as it moves up the food chain. A big tuna or shark may have 10+ times more mercury than a small fish it eats.

Age and size matter: Older, larger fish have had more time to accumulate metals, so they’re generally more contaminated than younger species.

Why Marine Fish Have Higher Levels

In ocean sediments, bacteria convert inorganic mercury into methylmercury—a highly toxic organic form that the body absorbs easily. Freshwater fish typically have much lower mercury levels than marine fish.

What Are the Health Risks?

Mercury: Primarily damages the nervous system. High exposure can cause tremors, memory loss, difficulty concentrating, and in developing fetuses and children, learning disabilities and developmental delays.

Lead: Decreases learning ability, causes developmental problems in children, and raises blood pressure in adults.

Cadmium: Accumulates in kidneys, potentially causing kidney damage with long-term exposure.

Arsenic: Can cause skin lesions, cancer, and cardiovascular disease with long-term exposure.

⚠️ Most Vulnerable Groups

Pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children are at greatest risk because:

• The developing nervous system is especially sensitive to mercury

• Children absorb and retain mercury more efficiently than adults

• Lower body weight means contaminants are more concentrated

• Developmental windows for learning are critical during early childhood

Mercury Levels in Common Fish

The FDA and EPA use mercury concentration (measured in parts per million or ppm) to categorize fish safety:

| Fish Type | Mercury Level (ppm) | Risk Category | Safe Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avoid (High Mercury) | |||

| Shark | 0.8–1.6 | High | Avoid or rarely |

| Swordfish | 0.995 | High | Avoid |

| King Mackerel | 0.73 | High | Avoid |

| Bigeye Tuna | 0.54–0.68 | High | Avoid or limit |

| Tilefish | 0.14 | High | Avoid |

| Moderate Mercury | |||

| Albacore Tuna | 0.32 | Moderate | 1 serving/week |

| Lingcod | 0.5 | Moderate | 1 serving/week |

| Sea Bass | 0.24 | Moderate | 1–2 servings/week |

| Lower Mercury (Best Choices) | |||

| Salmon (wild) | 0.05–0.06 | Low | 2–3 servings/week |

| Anchovies | 0.05 | Low | 2–3 servings/week |

| Sardines | 0.013 | Low | 2–3 servings/week |

| Flounder | 0.049 | Low | 2–3 servings/week |

| Shrimp | 0.009 | Low | 2–3 servings/week |

What Are the Official Safety Guidelines?

FDA and EPA Recommendations

For pregnant women, nursing mothers, and young children (ages 1-11):

• Avoid: Shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish

• Eat up to 12 ounces (about 2–3 servings) per week of lower-mercury fish and shellfish

• Choose a variety of fish, don’t eat the same one every day

For adults: The same guidelines apply, though the risk is lower. Pregnant women should be especially cautious.

FDA/EPA Reference Dose for Mercury

The FDA’s reference dose is 0.1 micrograms per kilogram of body weight per day. This is the amount of mercury experts consider safe for long-term exposure.

Example: A pregnant woman weighing 150 lbs (68 kg) can safely consume approximately 6.8 micrograms of mercury per day. This means she should limit high-mercury fish consumption significantly.

EFSA (European) Standards

Europe sets maximum mercury levels at 0.5 mg/kg for total mercury in fish muscle tissue. Studies show some marine fish exceed this limit, while freshwater fish typically stay well below it.

How to Reduce Your Exposure to Heavy Metals

1. Choose Lower-Mercury Fish

Eat more salmon, sardines, anchovies, shrimp, and flounder. These are consistently low in mercury and high in omega-3 fatty acids.

2. Limit High-Mercury Fish

Avoid shark, swordfish, king mackerel, and tilefish entirely. Limit albacore tuna and bigeye tuna to once per week.

3. Vary Your Choices

Don’t eat the same type of fish every day. Different species accumulate different metals at different rates. Variety reduces your cumulative exposure.

4. Choose Source Wisely

Wild-caught Alaskan salmon consistently tests low for mercury. Freshwater fish from clean sources are generally safer than marine fish. Check local fish advisories for your area—some bodies of water have higher contamination.

5. For Vulnerable Groups

Pregnant women and young children should prioritize low-mercury options and limit total fish consumption to the FDA’s recommended amounts (12 ounces per week).

6. Don’t Avoid Fish Entirely

Fish are rich in protein, omega-3 fatty acids, and other nutrients. The health benefits of eating fish outweigh the risks when you choose wisely and follow safety guidelines.

The Bottom Line

Heavy metals in fish are a real but manageable concern. Mercury, lead, and cadmium naturally accumulate in fish, especially large predatory species and marine fish. This happens through a process called biomagnification.

Scientific evidence is clear: Following FDA and EPA guidelines significantly reduces your risk. Eating 2–3 servings per week of lower-mercury fish (salmon, sardines, shrimp) is safe for most adults and provides substantial health benefits.

You can feel confident about fish consumption when you:

• Choose lower-mercury varieties

• Limit high-mercury species

• Vary your selections

• Pay extra attention if pregnant or caring for young children

Fish remains one of the healthiest protein sources available—just make informed choices about which fish to eat and how often.