How Is Ham Made?

From raw pork leg to cured, smoked delicacy through salt, time, and precision.

The Overview

Ham is the hind leg of a pig prepared as food through a curing process that involves salting, sometimes brining, and optionally smoking to preserve the meat while developing distinctive flavor.

The manufacturing process takes weeks to months depending on the ham type—commercial “city hams” use accelerated wet-curing methods taking days, while traditional country hams require months of dry-curing and aging.

Here’s exactly how fresh pork transforms into the iconic cured meat through salt chemistry and carefully controlled time.

🥘 Main Ingredients & Curing Agents

• Fresh pork hind leg

• Salt (primary curing agent)

• Sugar

• Sodium nitrite or nitrate (for color and preservation)

• Water (for wet brining)

• Spices (optional)

• Smoke (optional)

Step 1: Pork Selection & Preparation

Fresh pork hind legs (hams) are selected from butchered pigs, typically weighing 12-20 pounds depending on the breed and ham type desired.

The legs are trimmed to remove excess skin, excess fat, and bone fragments while retaining the protective fat layer and bone that add flavor during curing.

Trimmed hams are inspected for quality—color, texture, absence of defects—before moving to the curing phase.

Step 2: Curing Method Selection

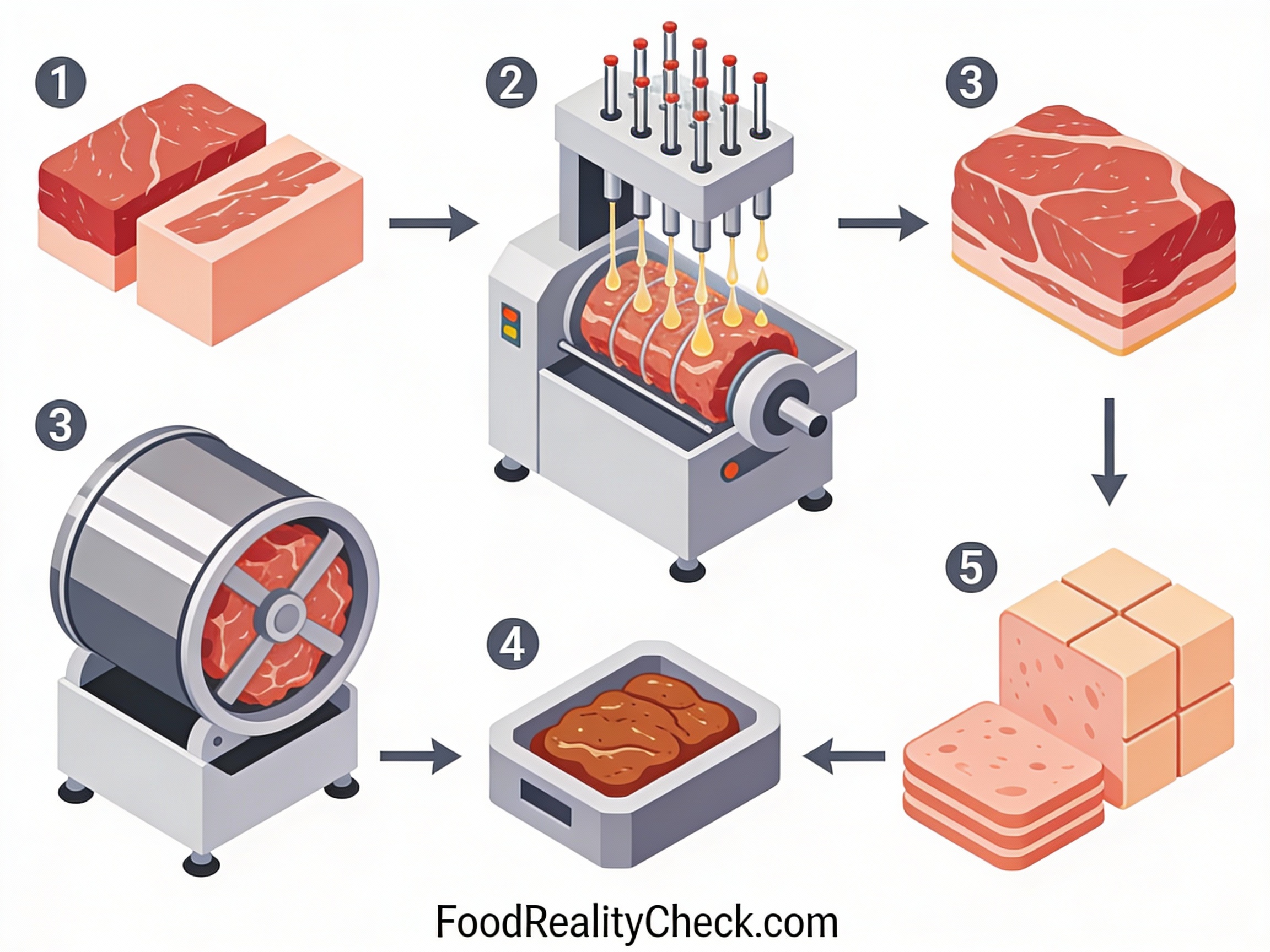

Two primary curing methods exist: dry curing (traditional, slower) and wet curing/brining (commercial, faster).

Dry curing involves rubbing salt directly onto the meat and letting it cure for 2-3 days per pound in refrigerated rooms—a 15-pound ham requires 30-45 days.

Wet curing involves injecting a brine solution (salt, sugar, water, curing agents) into the meat and soaking it for 4 days per pound, accelerated by pressure injection—a 15-pound ham requires 40-60 days with injection, or 60+ days by soaking alone.

Step 3: Dry Curing (Traditional Method)

For dry-cured hams (country hams, prosciutto), salt is thoroughly rubbed into the meat surface by hand or in mechanical tumblers.

The salt penetrates the meat, drawing out moisture through osmosis while simultaneously killing spoilage bacteria and creating an inhospitable environment for pathogens.

Hams are stored flat in cool, humid rooms (50-55°F / 10-13°C, 80-85% humidity) for 1-2 weeks, then hung vertically as the curing process continues.

Step 4: Wet Curing / Injection Brining (Commercial Method)

For commercial “city hams,” a brine solution (water, salt, sugar, sodium nitrite, phosphates, and spices) is mixed in large tanks.

Pork legs are placed in automatic injection pumps with multiple perforated needles that penetrate the meat, distributing brine evenly throughout.

The injection typically brings the ham to 110-120% of its original weight—essentially pumping in a significant amount of flavorful liquid.

Step 5: Curing Duration in Tanks

Injected hams are placed in large stainless steel tanks with additional brine and allowed to cure submerged at 35-40°F (2-4°C) for 2-4 weeks.

During this time, salt gradually penetrates from the surface toward the center of the meat—eventually reaching the deepest layers where it prevents botulism and spoilage.

The brine is continuously monitored for proper salt concentration and pH to ensure food safety and quality.

Step 6: Post-Curing Washing & Rinsing

After curing is complete, hams are removed from tanks and rinsed under cold running water to remove excess salt from the surface.

This washing ensures the final product isn’t excessively salty while retaining the interior salt penetration necessary for preservation and flavor.

Hams are patted dry and inspected for proper color, texture, and absence of defects.

Cooking & Smoking: Optional Enhancements

Step 7: Cooking (For Most Commercial Hams)

Most commercial hams are fully cooked at this stage, either in large industrial kettles or steam chambers heated to 160-165°F (71-74°C).

Cooking kills any remaining microorganisms, denatures proteins (making the meat firmer), and develops flavor through the Maillard reaction.

Cooking time depends on ham size—typically 20-30 minutes per pound, with continuous temperature monitoring to ensure the center reaches 160°F (71°C) internal temperature.

Step 8: Smoking (For Premium Varieties)

For smoked hams (country hams, hickory-smoked, applewood, etc.), cured hams are placed in smoking chambers where they’re exposed to smoke from hardwood (hickory, apple, oak) for 12-48 hours.

Smoke penetrates the meat surface, depositing hundreds of flavor compounds while also providing additional preservation through antimicrobial smoke components.

Temperature during smoking is carefully controlled (170-225°F / 77-107°C depending on desired level) to prevent case hardening (outer layer cooking faster than interior).

Step 9: Cooling & Rest Period

After cooking and/or smoking, hams are cooled in climate-controlled rooms to near-room temperature to solidify fats and stabilize the meat’s structure.

Some premium hams are aged for 6-12 months post-cooking in cool, humid rooms, allowing flavors to mature and intensify through enzymatic breakdown of proteins and fats.

This aging step is particularly important for country hams, where it develops the deep, concentrated flavor that commands premium prices.

Processing: Trimming, Slicing & Packaging

Step 10: Trimming & Shaping

Cooled hams are inspected and trimmed to remove excessive fat, rind, and any dried or discolored surface areas.

Whole hams may be portioned into roasts (larger cuts for home cooking) or cut into smaller sections for processing into sliced ham.

Trimmed hams are inspected for final quality and consistency before proceeding to slicing.

Step 11: Slicing on Automated Equipment

For packaged sliced ham, trimmed hams are placed on high-speed automated slicers with oscillating blades or continuous cutting surfaces.

Slicers are calibrated to produce consistent slice thickness—typically 2-3mm for deli-style ham—with 99% accuracy maintained throughout production.

Modern slicers process entire hams at rates of 200-500 slices per minute, with automatic rejection systems removing any off-thickness or defective slices.

Step 12: Portioning & Stacking

Sliced ham is automatically counted and stacked into portions (typically 100-200g or 3.5-7oz per package) using robotic stackers.

Slices are shingled (overlapped at slight angles) or interleaved (alternating orientation) to create an attractive presentation and facilitate separation during consumer use.

Portioned stacks are placed into film or plastic trays and conveyed to the packaging line.

Step 13: Vacuum Sealing & Modified Atmosphere Packaging

Portioned ham in trays is fed into vacuum sealing machines that remove air from the package before sealing with a lid or film.

Vacuum sealing removes oxygen, preventing oxidation (which causes color loss and rancidity) and inhibiting aerobic bacteria growth.

Some premium producers use modified atmosphere packaging (MAP)—replacing the removed air with nitrogen or carbon dioxide mixtures—to further extend shelf-life to 30+ days while maintaining flavor and color.

Step 14: Labeling & Coding

Sealed packages move to labeling machines that apply product labels, nutrition facts panels, ingredient lists, and barcodes at high speed.

Batch codes, production dates, and expiration dates are printed using thermal transfer or laser marking, enabling traceability and recall capability.

Each label is verified by vision inspection systems to ensure proper placement, legibility, and absence of defects.

Step 15: Case Packing & Cold Storage

Labeled ham packages are robotically packed into cardboard cases (typically 12-24 packages per case) and placed on pallets.

Cases are wrapped with plastic film and stored in refrigerated warehouses at 35-40°F (2-4°C).

Properly packaged and refrigerated ham remains fresh for 2-3 weeks, or up to 6+ months if frozen.

Step 16: Distribution & Retail Display

Packaged ham is loaded into refrigerated trucks and distributed to retailers, maintaining the cold chain throughout logistics.

At retail, ham is displayed in refrigerated deli cases where it’s typically kept at 32-40°F (0-4°C).

Consumers purchase packages and consume within the printed “best by” date for optimal quality and food safety.

Why This Process?

Salt curing is one of humanity’s oldest preservation techniques—salt creates an osmotic environment hostile to spoilage bacteria while simultaneously penetrating the meat and developing flavor.

Sodium nitrite prevents botulism (a deadly toxin-producing bacterium) while creating ham’s characteristic pink color and savory flavor profile.

Cooking and/or smoking inactivate pathogens and develop complex flavors through the Maillard reaction and smoke’s flavor compounds.

Aging allows enzymes to break down proteins into amino acids and fats into fatty acids, concentrating flavor dramatically.

What About Additives?

Commercial ham typically includes:

• Sodium nitrite (200 ppm maximum) – for preservation and color

• Phosphates (0.5% maximum) – to retain moisture

• Sugar or corn syrup – for flavor balance

• Spices – for taste

• Smoke flavoring – in some products

• Natural or artificial flavors – for depth

Premium hams may contain only salt, sugar, sodium nitrite, and optional spices—minimal additional additives.

The ingredient list reveals processing extent—fewer, simpler ingredients suggest less processing; longer lists with chemical names suggest more additive involvement.

The Bottom Line

Ham production is a carefully controlled curing and preservation process that dates back millennia, yet uses industrial precision to ensure food safety and consistency.

Whether dry-cured for months or wet-injected in days, the fundamental chemistry remains the same—salt penetrates the meat, killing spoilage organisms while developing distinctive flavor.

Now you understand exactly how a fresh pork leg transforms into ham through salt chemistry, optional smoking, cooking, and careful aging or processing.