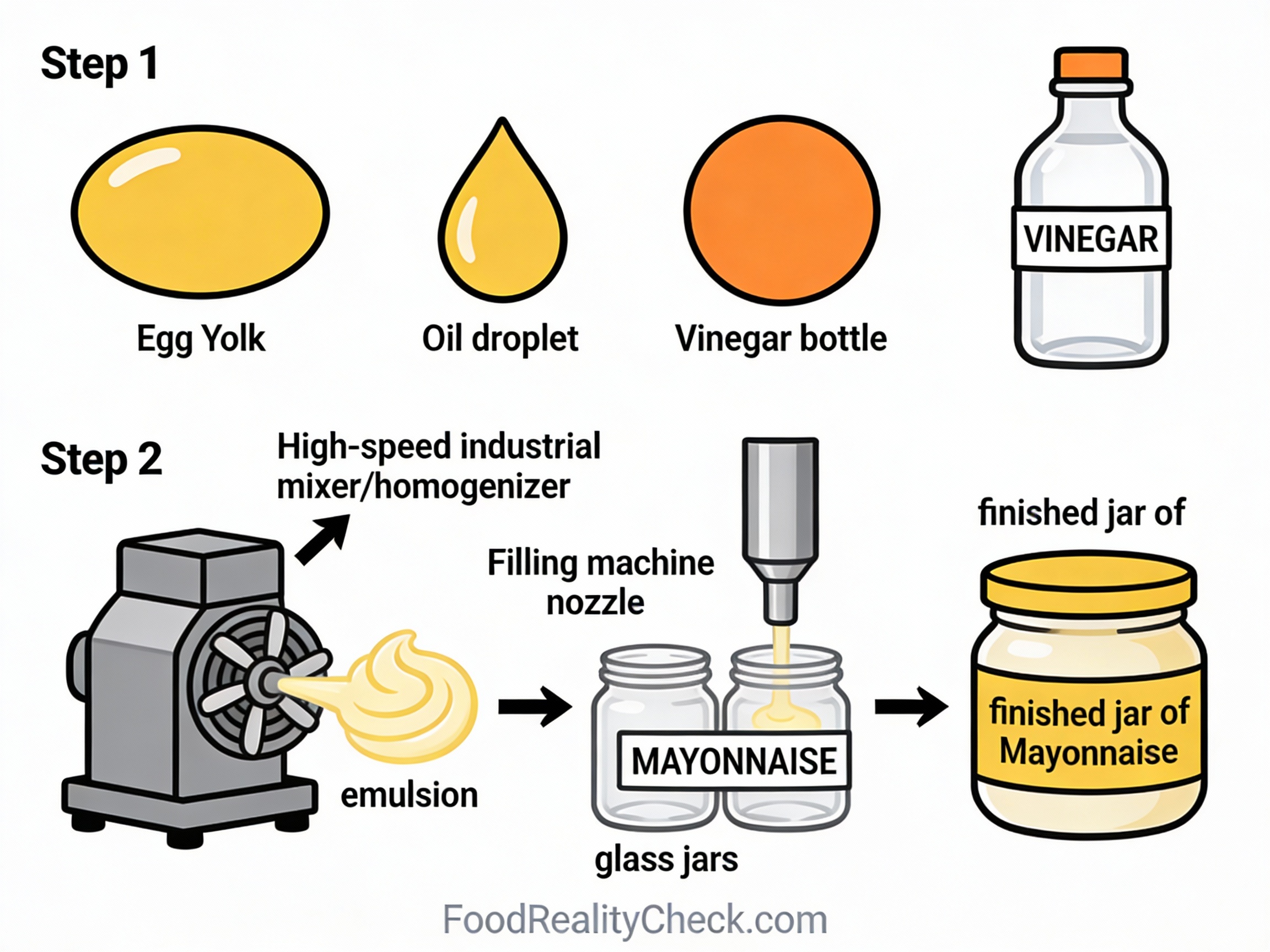

How Is Mayonnaise Made?

From oil and eggs to a creamy emulsion through science and precision.

The Overview

Mayonnaise is an oil-in-water emulsion containing 65-80% vegetable oil, egg yolk, vinegar, and seasonings that are blended together through precise mixing and emulsification.

The process relies on egg yolk’s natural emulsifying properties to hold oil and water together in a stable, creamy condiment that normally shouldn’t work—oil and water don’t mix, yet mayonnaise stays creamy for months.

Here’s exactly how oil, eggs, and vinegar transform into the perfect emulsion through chemistry and industrial precision.

🥘 Main Ingredients

• Vegetable oil (65-80% of final product)

• Egg yolk or pasteurized egg yolk (5-8%)

• Vinegar or lemon juice (3-4%)

• Mustard powder

• Salt

• Sugar

• Water

Step 1: Egg Yolk Preparation & Pasteurization

Fresh eggs arrive at the factory and are mechanically separated into yolks and whites using centrifugal separators or egg breaking machines.

The yolk liquid is pasteurized at 65-75°C (149-167°F) for 15-20 minutes to kill Salmonella and other pathogens while preserving lecithin and phospholipids—the natural emulsifiers that are the secret to mayonnaise’s stability.

Alternatively, pasteurized egg yolk powder or liquid egg yolk concentrate is used, requiring no further pasteurization.

Step 2: Water Phase Preparation

In a separate tank, the water phase is prepared by combining water, vinegar (or lemon juice), mustard powder, salt, sugar, and spices.

This acidic water phase is thoroughly mixed and may be gently heated to 80-85°C for 20 minutes to dissolve all powdered ingredients and ensure food safety.

The water phase is then cooled to 20-30°C before being introduced to the main mixing tank, or kept ice-cold (5°C) if the manufacturer uses a cold process to protect egg yolk.

Step 3: Egg Paste Formation

Pasteurized egg yolk is placed in a mixing tank with a portion of the water phase (typically one-third of the vinegar content) and mixed using a paddle-type mixer for 2-10 minutes.

This creates a thick, uniform egg paste that acts as the base emulsion—once oil is added, this paste will become mayonnaise.

The paddle mixer gently combines ingredients without creating excessive air incorporation, which would destabilize the final emulsion.

Step 4: Initial Emulsification at High Shear

The egg paste is transferred to the main mixing tank where a high-shear rotor-stator mixer is activated at high speed (up to 3,000 RPM).

The rotor and stator (one rotating, one stationary) create an intense shearing action, driving ingredients toward the narrow gap between them at centrifugal force.

This violent mixing breaks apart any agglomerates and prepares the mixture for oil incorporation.

Step 5: Gradual Oil Addition (The Critical Phase)

Vegetable oil is added very slowly—typically as a thin jet dispensed at 1-2 drops per second—into the high-shear mixer.

The high-shear action breaks the oil stream into microscopic droplets (2-4 microns in diameter) that are instantly surrounded by lecithin molecules from the egg yolk.

These oil droplets remain suspended in the water phase, creating a stable oil-in-water emulsion that is the foundation of mayonnaise.

Step 6: Controlled Oil Flow Rate

The speed at which oil is added is carefully controlled—too fast and the egg yolk’s emulsifying capacity is overwhelmed, causing the emulsion to break (separate into oil and liquid).

As the emulsion thickens with more oil, the feed rate is gradually increased, but never to the point where the texture becomes too thick for the mixer to handle.

Modern automated systems use pumps with precision flow control, typically maintaining a constant oil feed rate of 50-100 ml per minute depending on batch size.

Final Mixing & Pasteurization

Step 7: Vinegar-Salt Solution Introduction

As the final portions of oil are being added, the remaining vinegar-salt solution (kept cold at 15-16°C) is slowly introduced simultaneously.

The timing is critical—vinegar must be added gradually while oil is still flowing, never added all at once, which would break the emulsion.

The acid in vinegar adds flavor and helps preserve the product, while salt provides additional preservation and taste balance.

Step 8: Final Homogenization (Multiple Passes)

Once all ingredients are combined, the coarse emulsion is pumped through an industrial homogenizer or colloid mill operating at extremely high pressure (15,000+ PSI).

The mayonnaise passes through the homogenizer at least 2-3 times, with each pass breaking oil droplets smaller and more uniform.

Smaller, more uniform oil droplets create a thicker, creamier mouthfeel with better stability during storage—all key to premium quality mayonnaise.

Step 9: Quality Control Testing

Before pasteurization, samples are continuously pulled and analyzed for viscosity, pH, color, and texture using automated instruments.

Viscosity is measured by timing how long mayonnaise takes to flow through a standardized opening—the target is typically 2,000-3,500 centipoise.

pH is verified to ensure it’s around 3.8-4.0 (acidic enough to prevent bacterial growth) and color is confirmed to match the standard golden-yellow specification.

Step 10: Inline Pasteurization

The homogenized mayonnaise is pumped through a scraped-surface heat exchanger where it’s rapidly heated to 70-90°C for 15-60 seconds, depending on target shelf-life.

Higher temperature (85-90°C for 30 seconds) provides extended shelf-life but must be done carefully—egg yolk denatures above 65°C, potentially breaking the emulsion.

The continuous motion of scrapers in the heat exchanger ensures even heating and prevents thermal damage to this delicate emulsion.

Step 11: Rapid Cooling

Immediately after pasteurization, the mayonnaise is cooled back to 20-30°C using a second heat exchanger with cold water or glycol circulating on the opposite side.

Rapid cooling prevents further heat damage to egg yolk proteins and allows the emulsion to fully stabilize.

The entire process—heating to 85°C and cooling back down—takes only 1-2 minutes.

Step 12: Vacuum Deaeration (Optional but Premium)

Some premium manufacturers pass the cooled mayonnaise through a vacuum deaeration chamber to remove air bubbles and dissolved oxygen.

Removing air prevents oxidation (which darkens color and causes flavor loss) and creates a denser, creamier final product.

Deaeration is typically reserved for high-end mayonnaise where shelf-life and color retention are critical.

Step 13: Filling & Packaging

The finished mayonnaise is pumped into jars or squeeze bottles at high speed—modern filling lines process 300-500 containers per minute at 100% accuracy.

Containers are filled to precise weight (typically 473ml or 16oz), caps are applied and tightened, and labels are applied with nutrition information and expiration dates.

Quality checks remove any jars with improper fill level, damaged caps, or labeling defects.

Step 14: Cooling & Storage Before Distribution

Filled jars are cooled in climate-controlled rooms to 5-10°C before being packed into cases and stored in refrigerated warehouses.

Cold storage further stabilizes the emulsion and slows any microbial growth, extending shelf-life to 12+ months when properly maintained.

Mayonnaise is then distributed to retailers through refrigerated trucks, maintaining the cold chain throughout logistics.

Why This Process?

Egg yolk’s lecithin and phospholipids are nature’s emulsifiers—they stabilize the oil-in-water emulsion better than any synthetic additive.

High-shear mixing breaks oil into uniform droplets small enough to remain suspended indefinitely, creating a stable emulsion that doesn’t separate.

Careful control of oil flow rate prevents emulsion breakdown—exceed the yolk’s emulsifying capacity and the entire batch separates into oil and liquid.

Pasteurization extends shelf-life while maintaining emulsion integrity through careful temperature control.

What About Additives & Variations?

Most commercial mayonnaises contain:

• Soy lecithin (additional emulsifier) – for improved stability

• Modified starches or gums – for texture and consistency

• Preservatives (potassium sorbate) – to extend shelf-life

• Cellulose or other thickeners – for body and texture

• Spice extracts – for concentrated flavor

Low-fat mayonnaise (30-50% oil) requires additional thickeners and stabilizers to replicate the creamy texture of full-fat versions, making it technically a different formulation.

Eggless mayonnaise uses alternative emulsifiers like aquafaba (chickpea liquid) or mustard, but lacks the superior stability of egg-based formulations.

The Bottom Line

Mayonnaise production is a sophisticated emulsification process that transforms oil and water—two naturally incompatible liquids—into a stable, creamy condiment through careful mixing and the science of egg yolk’s natural emulsifiers.

The process requires precise control of ingredient addition rates, high-shear mixing to break oil into microscopic droplets, and careful pasteurization to ensure safety without breaking the emulsion.

Now you understand exactly how oil, eggs, and vinegar combine into mayonnaise through the chemistry of emulsification and the precision of industrial food processing.