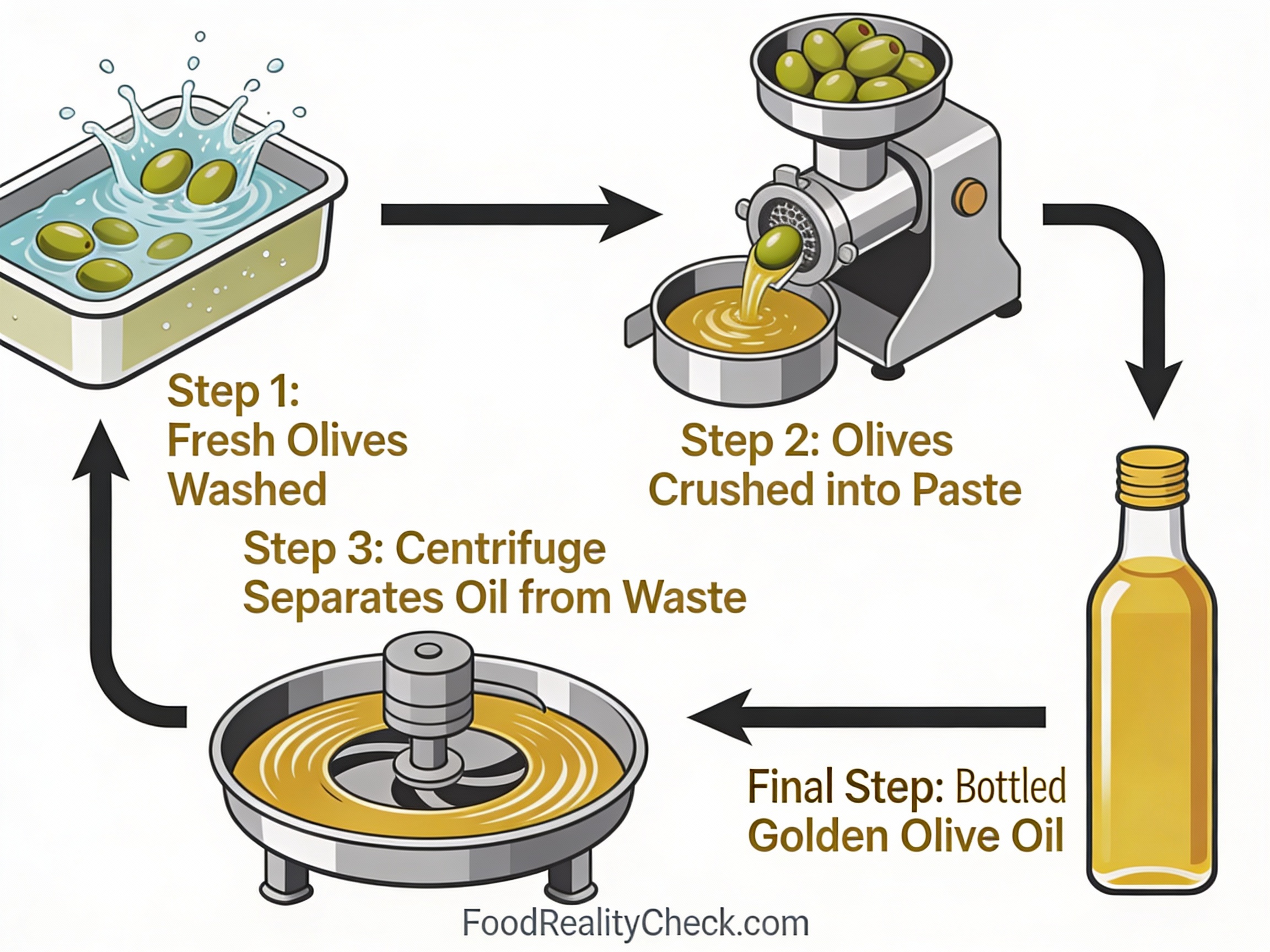

How Is Olive Oil Made?

From tree fruit to pressed oil through harvesting, crushing, pressing, and careful separation.

The Overview

Olive oil is made by harvesting olives from trees, washing and crushing them to break cell walls, pressing the pulp to extract oil, separating the oil from water and solids, and bottling the final product—all accomplished through mechanical pressing with minimal processing or chemical intervention.

The manufacturing process is remarkably simple compared to other oils—olive oil requires no refining, no chemical extraction, no heat treatment to extraction (in extra virgin and virgin grades)—making it one of the few foods that is simply pressed fruit juice.

Here’s exactly how olives transform into oil through mechanical crushing and pressing.

🥘 Main Ingredients & Materials

• Fresh olives (ripe or unripe depending on desired oil type)

• No other ingredients (100% pure olive oil)

• Water (for washing, removed during processing)

• Inert gases (nitrogen, used to prevent oxidation in storage)

Step 1: Olive Harvesting

Olives are harvested from trees once they reach the desired ripeness—earlier harvest (green olives) produces green, peppery oil; later harvest (ripe, dark olives) produces golden, buttery oil.

Harvest timing is critical for quality—overripe olives develop off-flavors and degraded oil; underripe olives are harder to press.

Harvesting is done either by hand (premium producers, slower but gentler on fruit) or mechanical shakers that vibrate trees, causing olives to fall into nets below (faster, more economical).

Step 2: Transport & Storage (Brief Holding Period)

Harvested olives are transported to the oil mill (pressing facility) as quickly as possible—ideally within 2-4 hours of harvest.

Delays degrade oil quality through oxidation and fermentation—olives begin to deteriorate immediately after harvest.

Premium producers (“extra virgin” producers) process olives within hours of harvest; lower-grade producers may wait 24+ hours, creating off-flavors and lower quality oil.

Step 3: Washing & Cleaning

Fresh olives are washed in large tanks of cool water to remove leaves, twigs, dirt, and debris.

Washing is thorough—olives are rinsed multiple times until water runs clear.

Removing debris is critical—sticks and leaves would create bitter flavors and reduce pressing efficiency.

💡 Did You Know? Olives are roughly 20% oil by weight—meaning 100 kilograms of olives produce approximately 20 liters of oil. This is far higher than most oil crops (sunflower: 40-50%, soy: 18-20%), which is why olives are so efficient at producing oil. A mature olive tree can produce 20-50 kg of olives per year, yielding 4-10 liters of oil annually.

Step 4: Crushing (Mechanical Breaking of Cell Walls)

Washed olives are fed into large mechanical crushers (either traditional stone mills or modern steel crushers) that break the olive fruit into a thick paste.

Crushing breaks the cell walls, releasing oil that would otherwise remain trapped inside the fruit cells.

Modern crushers operate slowly (to prevent excessive heat generation from friction) and produce a uniform paste with no whole olives remaining.

Step 5: Paste Malaxation (Temperature-Controlled Mixing)

The crushed olive paste is transferred to a “malaxer”—a slowly rotating tank where the paste is gently mixed for 20-45 minutes at controlled temperature (27-30°C for premium oil, up to 35-40°C for lower grades).

Malaxation allows small oil droplets to coalesce into larger droplets that are easier to press out, dramatically increasing oil extraction efficiency by 2-5% compared to pressing immediately after crushing.

Temperature control is critical—higher temperatures increase extraction but degrade flavor compounds (oxidation); lower temperatures preserve flavor but reduce extraction.

Step 6: Pressing & Oil Extraction

The malaxed olive paste is placed in a large hydraulic press (either traditional spiral press or modern centrifugal press) that applies tremendous pressure (150-500 bar / 2,200-7,250 PSI) to squeeze oil out of the solid matter.

The pressure forces oil, water, and other liquids through the paste while solid matter (skin, pits, flesh) remains behind as “pomace.”

Pressing takes 30-60 minutes traditionally; modern centrifugal presses extract oil much faster (5-10 minutes).

Step 7: Oil-Water Separation (Decanting or Centrifugation)

The liquid extracted from pressing is a mixture of oil and water (roughly 20% oil, 80% water by volume)—they don’t mix but form separate layers due to different density.

Oil naturally floats to the top; water sinks to the bottom. This mixture is allowed to rest for 4-12 hours so oil and water separate naturally (decanting), or it’s processed immediately through a centrifuge.

Centrifuges spin at high speed (2,000-3,600 RPM) for 3-5 minutes, using centrifugal force to separate oil from water and solids much faster than gravity alone.

💡 Did You Know? The liquid extracted from pressing isn’t pure oil—it’s roughly 80% water and 20% oil plus suspended solids. Modern centrifuges separate these components in minutes; traditional gravity separation takes 12+ hours. This is why “fresh pressed” olive oil from traditional producers still contains small amounts of sediment and water—it’s separated by gravity, which is slower but considered more natural and flavor-preserving.

Step 8: Final Separation & Clarification

After initial centrifugation or gravity separation, the oil still contains trace amounts of water and fine sediment (polyphenols, proteins, carbohydrates).

For extra virgin and virgin oils (premium grades), this is left mostly untouched—the sediment is considered part of the traditional product and contributes to flavor.

For refined and light oils (lower grades), additional centrifugation or filtration through cloth or paper removes remaining sediment, creating crystal-clear oil.

Step 9: Storage & Resting (Optional, for Flavor Development)

Some producers allow freshly pressed oil to rest in stainless steel tanks for several weeks, allowing flavor to settle and stabilize.

This resting period (maturation) can enhance or mellow flavors depending on producer preferences.

Other producers bottle immediately after pressing for maximum freshness—the choice depends on desired final product characteristics.

Bottling, Labeling & Distribution

Step 10: Bottling Into Glass or Plastic Containers

Clarified olive oil is filled into bottles (typically 250ml, 500ml, or 1-liter glass bottles, or occasionally plastic) at 20-50 bottles per minute using automated filling machines.

Fill volumes are precisely controlled—modern equipment maintains accuracy to within ±5ml (about 1% of total volume).

For premium extra virgin oils, glass bottles are preferred (light-colored glass reduces light exposure that degrades oil); budget oils sometimes use PET plastic which is cheaper but less protective.

Step 11: Capping & Sealing

Filled bottles are immediately capped with either screw caps (more common) or cork closures (for traditional/premium products).

Proper sealing is critical—oxygen contact causes rancidity (oxidation of fatty acids), producing off-flavors.

Some premium producers use specially designed caps or inject nitrogen gas into the headspace before capping, further protecting against oxidation.

Step 12: Labeling & Grade Designation

Bottles are labeled with brand name, origin (country, region, or “country blend”), grade (“Extra Virgin,” “Virgin,” “Light,” etc.), harvest date (for premium oils), tasting notes, and nutritional information.

Grade designation is legally regulated—only oils meeting strict standards can be labeled “extra virgin” (coldpressed, no refining, <0.8% acidity) or “virgin” (coldpressed, no refining, <2% acidity).

“Pure olive oil” is refined oil, lower grade and quality. “Light olive oil” is heavily refined, tasteless, used for cooking rather than flavor.

Step 13: Case Packing & Warehousing

Labeled bottles are packed into cardboard cases (typically 6-12 bottles per case) and stacked on pallets.

Olive oil is stored in cool, dark conditions (10-18°C, darkness to prevent light-induced oxidation).

Proper storage extends shelf-life to 2+ years; exposure to light or heat degrades oil quality rapidly.

Step 14: Distribution & Retail Display

Packaged olive oil is distributed via ambient temperature trucks to retail stores, restaurants, and food service establishments.

In stores, olive oil is displayed in shelf-stable sections away from direct light (though some stores unfortunately display it under bright lights, which degrades quality).

Consumers purchase and consume within 2 years of harvest (indicated on premium bottles), or within several months of opening for best flavor.

Why This Process?

Mechanical pressing extracts oil without chemicals—no hexane solvents (used for seed oils), no bleaching, no deodorization (used for refined oils).

Temperature control during crushing and malaxation preserves delicate flavor compounds—higher temperatures increase extraction but degrade flavor through oxidation.

Gravity separation (decanting) is preferred by premium producers over high-speed centrifugation because it’s gentler on flavor compounds.

Cold-pressing (no heat) preserves polyphenols (antioxidants) and flavor compounds that would degrade at high temperature.

Olive Oil Grades & Quality Variation

Olive oil grades are strictly legally defined:

• Extra Virgin: Cold-pressed, <0.8% acidity, no refining, best flavor, most expensive

• Virgin: Cold-pressed, <2% acidity, no refining, good flavor, lower price

• Pure/Regular: Refined oil, chemically processed, mild flavor, low cost, good for cooking

• Light: Heavily refined, nearly flavorless, high smoke point, cheapest option

Quality varies tremendously within “extra virgin” grade—single-estate oils from premium producers taste dramatically different from bulk blended oils from multiple sources.

The Bottom Line

Olive oil production is one of the simplest food processing operations—olives are crushed, pressed, and the oil is separated from water and solids using only mechanical force and gravity.

No chemicals, no refining, no high heat in premium grades—just fruit juice in its purest form.

Now you understand exactly how olives become oil through mechanical crushing, pressing, and gravity separation—a process virtually unchanged for thousands of years.