Here’s what the science actually says. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) is one of the most studied food ingredients in history. Yet myths about it persist, largely because its reputation was destroyed by a hoax published in 1968.

The Internet Myth

You’ve probably heard of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”—a purported condition caused by MSG that produces headaches, numbness, chest pain, and nausea.

You might have seen claims that MSG is an excitotoxin that damages your brain and causes neurological disease.

Wellness sites warn that MSG causes obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

Health food stores sell “MSG-free” products as if it’s toxic.

But here’s the thing: the entire foundation of MSG fear is built on something that never actually happened.

The Origin of the Fear (It’s Literally a Prank)

In 1968, Robert Ho Man Kwok sent a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine describing symptoms he experienced after eating Chinese food: weakness, numbness, heart palpitations, and chest pain. He called it “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.”

The journal published it. Other readers sent in anecdotal letters describing similar symptoms. The media covered it extensively, and fear spread globally.

Here’s the problem: It was a prank. Kwok later admitted he wrote it to see if the journal would publish letters without rigorous evidence. And it did. What should have been dismissed as a single anecdote became the foundation for 50+ years of MSG fearmongering.

The term is now so stigmatized that it was removed from medical dictionaries and Merriam-Webster added an addendum noting it’s offensive and disproven.

What the Regulatory Experts Say

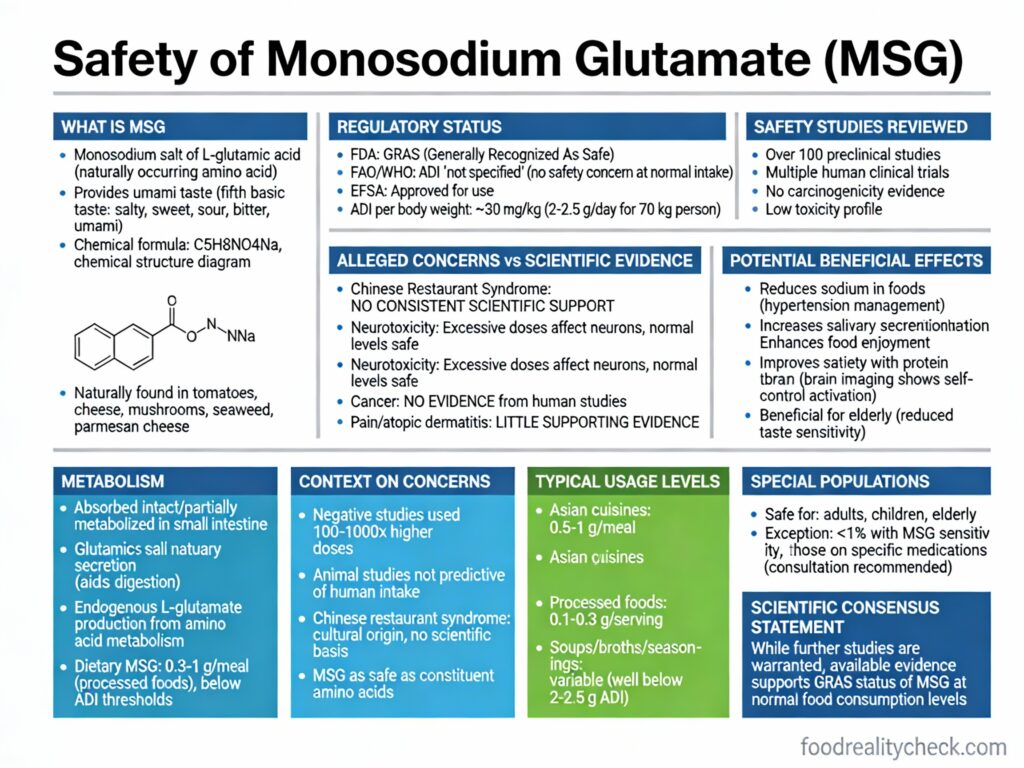

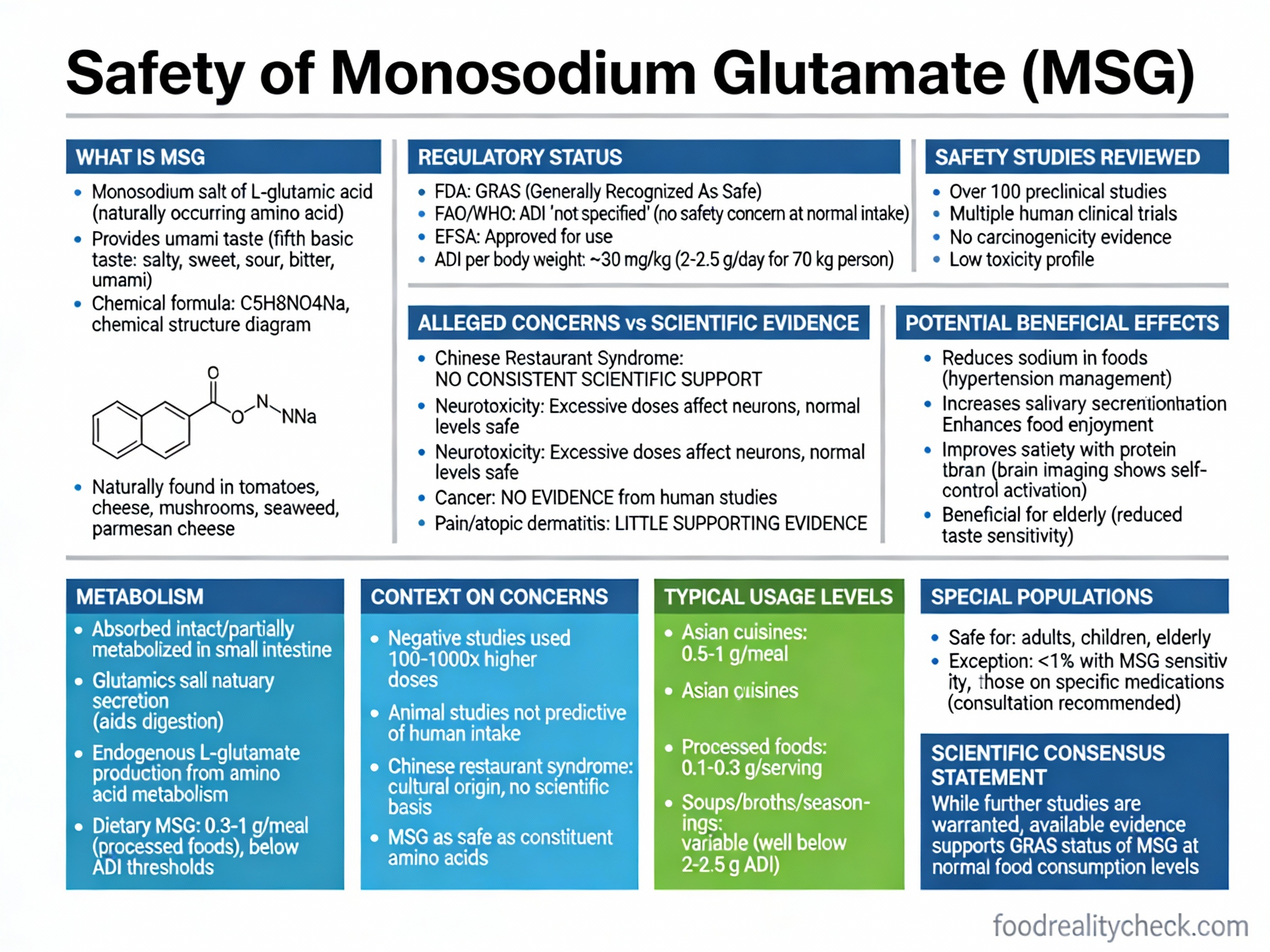

The FDA says: MSG is “Generally Recognized as Safe” (GRAS). The agency has received complaints about MSG for decades but “were never able to confirm that the MSG caused the reported effects.” Even when some people claim sensitivity to MSG, controlled studies with placebos show no consistent reaction.

The EFSA says: Food-grade MSG is safe for consumers. The European Food Safety Authority set an Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI) of 30 mg/kg of body weight per day—meaning a 70 kg adult could safely consume over 2,100 mg of MSG daily.

The WHO says: The Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) confirms MSG is safe for consumption at normal dietary levels.

The consensus is clear: For the general population, MSG at typical consumption levels presents no documented safety risk.

What the Science Shows

The research on MSG divides into three categories: brain effects, sensitivity/headaches, and weight gain. The evidence tells very different stories for each.

Can MSG Damage Your Brain?

This is where the “excitotoxin” scare comes from. Some animal studies used extreme doses of injected MSG (injections, not food) and found neurological damage. But here’s the critical finding: the blood-brain barrier blocks glutamate from entering the brain from the bloodstream.

When humans eat MSG, blood glutamate levels may rise temporarily (about 11-fold above baseline after consuming a high dose on an empty stomach), but this doesn’t increase brain glutamate concentrations. In studies using the most powerful brain markers available, MSG had zero effect on brain function, hormone secretion, or neural activity. A 3-generation study of mice fed diets containing 1-4% MSG (far exceeding human consumption) found no neurological effects.

Result: Dietary MSG does not penetrate the brain and does not cause neurological damage.

Does MSG Cause Headaches or “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome”?

The 1995 FASEB report acknowledged that some sensitive individuals might experience mild, temporary symptoms (headache, numbness, flushing, tingling) if they consume 3+ grams of MSG without food. But this is critical: a typical serving of food containing added MSG has less than 0.5 grams.

Double-blind studies—where neither the researcher nor participant knows who got MSG—consistently fail to reproduce the effect. When people believe they’re getting MSG but aren’t, they report symptoms anyway. This is the nocebo effect, not MSG toxicity. When “no MSG” signs appear in restaurants, they actually strengthen the nocebo effect by reinforcing the belief that MSG is dangerous.

Result: There is no scientific evidence supporting “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” Reported symptoms are likely placebo/nocebo effects.

Does MSG Cause Weight Gain?

This is the one area where human evidence exists—and it’s genuinely concerning, though complicated. A 2008 study of 752 Chinese adults found that people consuming the highest amounts of MSG had 2.1-2.75 times higher odds of being overweight, even when controlling for total calories eaten and physical activity.

However: This was observational (correlation, not causation), self-reported dietary intake, and involved much higher MSG consumption (0.33g/day average) than typical Western diets (estimated 0.55g/day globally, much lower in non-Asian countries). Some animal studies show weight gain in MSG-treated animals even with equal food intake, suggesting MSG might interfere with satiety signals or metabolism. But many other human studies show no association, and some find no effect when MSG consumption is moderate.

Result: There may be an association between high MSG intake and weight gain, but evidence is inconsistent and limited. The effect appears dose-dependent and may not apply to typical Western consumption levels.

Why Is There So Much Fear?

The MSG panic originated from a published letter that was literally a joke—a prank that became accepted as fact through media repetition and the human tendency to believe false information after exposure (“illusory truth effect”).

It was amplified by racism. The stigma around MSG became culturally tied to Asian food and Asian restaurants, creating a subtle but persistent stereotype that Asian cuisines are inherently unhealthy. This is why the recent resurgence of “reclaiming MSG” has become a cultural justice issue for many Asian Americans.

Preclinical studies showing MSG damage used unrealistic doses and injection routes. The distinction between these artificial conditions and real-world eating was lost in popular coverage.

Real Concerns (If Any)

MSG isn’t perfect, and blanket statements about safety aren’t nuanced enough for everyone.

⚠️ Potential weight gain concern

If you’re trying to lose weight or manage obesity, high MSG intake (particularly in Asian cuisines with added MSG) may contribute to overeating. The evidence is mixed, but the risk appears real enough to warrant attention if this is a health priority for you. Moderate MSG consumption in typical processed foods is unlikely to cause problems.

⚠️ Individual sensitivity

Although double-blind studies show no consistent effect, some people genuinely report feeling worse after eating MSG-containing foods. This might be a genuine sensitivity in a small subset of the population, or it might be nocebo. Either way, if you experience symptoms, avoiding high-MSG foods is reasonable—not because MSG is inherently dangerous, but because your experience matters.

For most healthy people without special concerns, MSG at normal dietary levels is safe and causes no documented problems.

The Safe Amount

The EFSA’s ADI is 30 mg/kg body weight per day. For a 70 kg adult, this equals 2,100 mg (2.1 grams) of pure MSG daily.

Typical global consumption is around 0.55 grams per day—less than 1/4 of the regulatory limit. Even in China, where MSG use is highest, average intake is approximately 0.33 grams per day.

To exceed the safety threshold, you’d need to deliberately overload on foods heavily fortified with MSG. Normal eating patterns won’t get you there.

The Bottom Line

MSG is safe for the general population at normal consumption levels, according to the FDA, EFSA, and WHO—backed by over 50 years of safety research and thousands of scientific studies.

The “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” panic originated from a pranked letter that the journal published without verification. The fear persists due to media repetition and the nocebo effect.

The science says: MSG does not damage your brain, does not consistently cause headaches, and does not directly cause weight gain at typical dietary levels. However, some evidence suggests high intake may be associated with obesity, though this remains contested and likely dose-dependent.

You can feel confident eating MSG-containing foods. If you’re concerned about weight gain or suspect personal sensitivity, you have reason to monitor your intake—but this is different from MSG being objectively dangerous.

The deeper truth: The MSG panic reflects how a single false claim, amplified by media and tied to ethnic prejudice, can override decades of scientific evidence. It’s a powerful reminder to be skeptical of food fears and to look at the actual research before deciding what to avoid.