Fermented salami represents centuries-old preservation meeting modern food safety science. Understanding how beneficial bacteria create safety while developing complex flavors reveals why fermented products represent both tradition and controlled preservation.

Fermentation Basics in Salami

Salami fermentation relies on lactic acid bacteria (LAB)—primarily Lactobacillus and Pediococcus species—consuming sugars (glucose, dextrose added during formulation) and producing lactic acid as byproduct. As LAB multiply, acid accumulates, progressively lowering pH. The combination of salt (reducing water activity), acid (lowering pH), and competing LAB creates an environment where pathogens cannot grow. This multi-layered safety approach—using salt, fermentation, and drying together—produces the most stable cured meat products.

Fermentation typically takes 2-4 weeks at controlled temperature and humidity. As pH drops (typically reaching 4.5-5.0), the environment becomes progressively more hostile to pathogens. Listeria monocytogenes (the primary post-processing contamination concern) cannot grow below pH 4.5, and cannot grow below specific water activity levels achieved through drying. Proper fermented salami achieves safety through multiple mechanisms operating simultaneously.

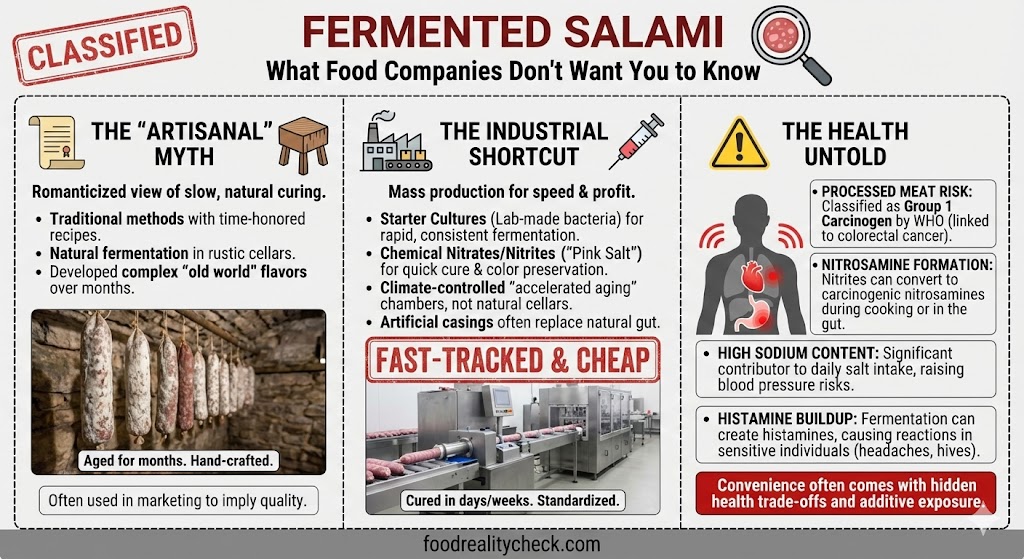

Wild Fermentation vs Starter Cultures

Wild fermentation: Traditional production relies on naturally present bacteria in the meat, environment, and equipment. These bacteria ferment unpredictably—sometimes producing excellent products, sometimes failing or creating off-flavors. This variability reflects the traditional reality: some producers succeeded (preserving their methods), others failed (losing the knowledge). Success required experience, intuition, and luck.

Starter cultures: Modern producers add selected LAB strains (typically Lactobacillus plantarum, Pediococcus pentosaceus) in controlled amounts. These bacteria ferment predictably, consistently reaching target pH within expected timeframes. This removes the guesswork, producing consistent products reliably. The trade-off: selected starter cultures may produce slightly simpler flavor profiles than wild fermentation with complex microbiota, though this is debated.

How Fermentation Creates Safety

Fermentation develops safety through three mechanisms operating simultaneously: (1) pH reduction: Lactic acid production lowers pH, with pathogenic bacteria becoming inhibited progressively as pH drops. (2) Antimicrobial compound production: LAB produce bacteriocins—protein compounds inhibiting competing bacteria. (3) Water activity reduction: Combined with drying and salt, water activity drops below 0.92, where pathogens cannot multiply. Together, these mechanisms create multiple obstacles for pathogen survival, explaining why properly fermented salami is remarkably stable.

Fermentation also breaks down nutrients that pathogens require. Combined nutrient depletion, hostile pH, antimicrobial compounds, and reduced water activity create virtually impossible conditions for pathogens. This is why traditional fermented sausages can be stored at room temperature for months without refrigeration.

Complex Flavor Development

LAB metabolism produces numerous flavor compounds beyond simple lactic acid. Different species and strains produce different compounds—some producing acetic acid, others producing other organic acids; some producing aroma compounds through ester production. The complexity reflects microbial diversity. Extended fermentation (4 weeks versus 2 weeks) allows more complete flavor development. Yeast and molds growing on product surfaces contribute additional flavors. The result is flavor complexity impossible to achieve through salt and smoke alone.

Umami flavors develop through protein breakdown producing glutamate and related compounds. These savory, complex flavors are what distinguish premium fermented salami from simple salt-cured products. The development requires time—generally, 3-4 weeks minimum for basic fermentation, though extended aging (months) develops progressively more complex flavors.

Traditional Production Methods

Traditional salami production begins with meat selection and grinding, mixing with salt (typically 2-3% by weight), sugar (0.5-1%), spices, and nitrates or nitrites. The mixture is stuffed into casings and hung in temperature/humidity-controlled rooms (traditionally cool, natural conditions). Fermentation begins with natural bacteria, typically producing visible mold on the surface. Proper fermentation produces beneficial white/grayish mold; improper fermentation produces unwanted pathogens or spoilage molds.

Fermentation duration depends on desired final pH and flavor intensity. Quick fermentation (2-3 weeks) produces milder flavor and shorter drying time. Extended fermentation (4-8 weeks) develops more complex flavor but requires more time and space. Climate variation (seasonal temperature/humidity differences) creates vintage variation—spring salami differs subtly from fall salami. This variation is tradition’s character, though modern producers increasingly control conditions for consistency.

Modern Controlled Fermentation

Modern producers maintain temperature at 20-25°C and humidity at 70-85%, creating consistent fermentation conditions. Starter cultures ensure rapid, predictable pH reduction. Multiple-point fermentation monitoring (measuring pH progression) guides decisions about when fermentation is complete. Some producers use enzymatic analysis to confirm proper protein and fat breakdown. These controls eliminate spoilage risk and guarantee food safety.

The result: consistent products reliably achieving safety and desirable characteristics. The trade-off: potential loss of vintage variation and complex microbiota flavor from wild fermentation. However, most modern producers achieve excellent quality through careful starter culture selection and controlled conditions. The consistency enables professional quality assurance and reliable product safety.

Challenges of Home Production

Home fermented salami production faces significant challenges: temperature control (home environments fluctuate), humidity control (difficult without dedicated space), starter culture sourcing (specialty ingredients), food safety risk assessment (determining when pH is adequate), and spoilage management (identifying problems). Additionally, home conditions may harbor undesirable bacteria creating safety risks. These factors explain why commercial fermented salami is far safer than home production.

For those interested in home fermentation, following detailed, researched recipes, using quality starter cultures, and maintaining proper conditions are essential. However, the risk profile is different from commercial production. Many people produce successful home fermented salami; others encounter problems. Commercial production controls remove this uncertainty.